This issue was originally printed in our Fall 2019 issue.

As the production of methamphetamine increases exponentially, San Francisco struggles to look for solutions.

There has been a dramatic increase in methamphetamine abuse in recent years in the United States of America. While the opioid crisis has received mass media attention, the mainstream news and Americans as a whole are unaware of the rising threat of meth on the horizon. Meth is back on the streets in purer forms and is more accessible than ever before, and its effects can be seen in San Francisco.

Methamphetamine is not a new issue in the United States. The grapple with methamphetamine abuse reached a peak in the mid-2000s, when domestic labs in Western, Midwestern, and Southern states were the main suppliers. The national ban of over-the-counter sales of cold and allergy medicines that contain ingredients used to synthesize methamphetamine as well as additional state measures made it difficult for these domestic labs to function, and the use of methamphetamine dropped for a period.

In recent years, however, the task of making meth has been picked up by so-called “super-labs” run by drug cartels based in Mexico. While the domestic labs of the 2000s could produce many small batches, “super-labs” release hundreds of pounds of 90 to 95 percent pure meth a day. According to the United States Customs and Border Protection, there were 56,362 pounds of meth seized at the border in 2018, which is about a 285 percent increase since 2014. In contrast, the amount of drugs such as heroin and cocaine seized at the border has dropped. Once the methamphetamine floods into the U.S., its abundance and cheap price make it a tempting offer for underprivileged marginalized groups and struggling addicts. The rising epidemic is having a big impact on states in the Midwest and Pacific Northwest, and it is especially evident in San Francisco.

Methamphetamine addiction has led to grave consequences in San Francisco. According to Erin Allday, a reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle, “Methamphetamine overdose deaths doubled over the past decade, even as opioid fatalities stabilized. … Meth-related emergency room visits skyrocketed more than 1,200 percent from about 150 in 2008 to nearly 2,000 in 2016.” In addition, the San Francisco Department of Public Health reports that about 50 percent of the 7,000 annual psychiatric emergency visits at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital are patients that are high on meth.

How does methamphetamine affect users and why is it dangerous? In the short term, meth increases wakefulness and physical activity; brings a euphoric rush; and leads to an irregular heartbeat, increased respiration, and higher blood pressure. In cases of overdose, it can lead to hyperthermia and convulsions, which will lead to death if untreated. As methamphetamine is a highly addictive stimulant, constant users will develop tolerance to its euphoric effects and will take more and more to produce the same feeling. In addition, constant meth users can experience severe anxiety, confusion, violent episodes, and psychotic behavior such as paranoia, hallucinations, and delusions. These psychotic symptoms can persist even long after someone has stopped using meth.

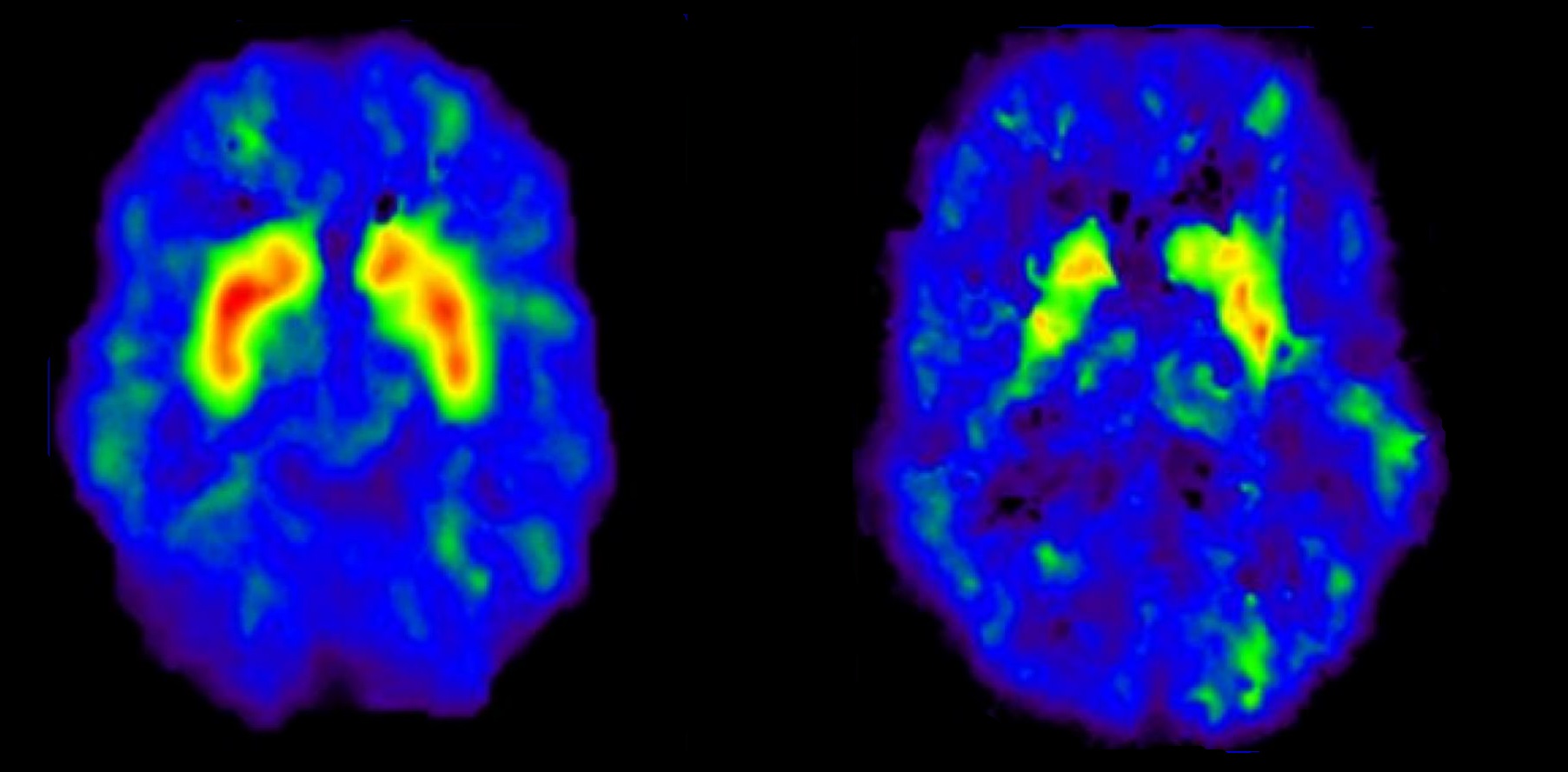

Neuroimaging studies of the brains of meth abusers have shown that meth changes the structure and function of the parts of the brain associated with emotion, memory, verbal learning, and the removal of damaged neurons. Although the studies revealed that some parts of the brain will go back to normal after prolonged abstinence from the drug, much of the damage is irreversible. In addition, the use of methamphetamine has been correlated to an increased risk for stroke and Parkinson’s disease. Constant meth users also experience tooth decay and skin sores.

Methamphetamine addiction has a particularly devastating effect on the most vulnerable parts of the population. Many people who struggle with meth use are facing housing instability and financial issues. People who do not have a home to go to at night often report using methamphetamine to stay awake and protect themselves from the dangers that come with sleeping on the streets. Low-income individuals and recent immigrants are at risk to start using methamphetamine to alleviate the stress from socioeconomic instability. Barriers such as a lack of transportation and fear of authority prevent these folks from being able to access treatment.

To address this issue, the City and County of San Francisco has put together a methamphetamine task force, co-chaired by Mayor London Breed and Supervisor Rafael Mandelman. Other members of the task force include specialists in addiction research, public health representatives, and methamphetamine users. The goal of the task force is to come up with policy solutions that would increase aid to users and guide them into recovery instead of pressing criminal charges.

Side-by-side comparisons of two brain scans measuring dopamine transporter activity are shown above. On the left, the scan of a normal control shows increased dopamine transporter activity. On the right, the scan of a methamphetamine abuser shows decreased dopamine transporter activity and compromised mental function. PHOTO BY THE NIH/NATIONAL INSTITUTE ON DRUG ABUSE

According to Erin Mundy, Mandelman’s legislative aide who focuses on homelessness and substance abuse, “The meth task force is an opportunity for everyone to get into one room and share ideas. There’s a lot of amazing work going on, but people aren’t always communicating with each other. The meth task force is the exact way to do so.” Other than increasing access to treatment, the task force aims to improve street response to 911 calls for people exhibiting signs of meth-induced psychosis. Often, these people are not in need of the police but rather a well-trained professional to de-escalate the situation.

The task force is also working on public education campaigns and creating focus groups for users and people close to them. “We need to have an appropriate response so that the community feels safe and people in crisis have the resources they need,” Mundy states. “We are hoping to be a model for other cities so that if the [methamphetamine] crisis spreads to other cities, they can look to San Francisco and the meth task force.”

In the meantime, various organizations and treatment programs in the Bay Area are doing their best to provide for the struggling community. These include the Positive Reinforcement Opportunity Project run by the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, which promotes incentive-based abstinence from methamphetamine use, and respite centers that provide counseling and guidance services.

Methamphetamine use has had a dramatic resurgence in the United States and has a particular impact on marginalized groups in San Francisco. Without the support of the community, these individuals will fall through the cracks and not get the support that they need. With increased education and the advocacy of the general public, methamphetamine users will be able to start on the path to recovery.